John Adams is well known for many roles — patriot, diplomat, second president of the United States, first vice president, husband of Abigail, and father of John Quincy (the sixth president). His link to the Library of Congress is less often cited. More often, the role of Thomas Jefferson in rebuilding its collection is recalled.

In 1980, an annex to the main Library building (the Jefferson Building) was renamed to commemorate the role Adams played in 1800 by signing a bill establishing “a reference library for Congress.” The original library, built with $5,000 appropriated by the legislature, was housed in the new Capitol Building in Washington, DC. But this collection was short lived.

In August 1814, invading British troops set fire to the Capitol, destroying much of the small library. It’s here that Jefferson steps into the story. The Library of Congress website notes:

Within a month, retired President Thomas Jefferson offered his personal library as a replacement. Jefferson had spent 50 years accumulating books, “putting by everything which related to America, and indeed whatever was rare and valuable in every science”; his library was considered to be one of the finest in the United States.

In offering his collection to Congress, Jefferson anticipated controversy over the nature of his collection, which included books in foreign languages and volumes of philosophy, science, literature, and other topics not normally viewed as part of a legislative library. He wrote, “I do not know that it contains any branch of science which Congress would wish to exclude from their collection; there is, in fact, no subject to which a Member of Congress may not have occasion to refer.”

In January 1815, Congress accepted Jefferson’s offer, appropriating $23,950 for his 6,487 books, and the foundation was laid for a great national library. The Jeffersonian concept of universality, the belief that all subjects are important to the library of the American legislature, is the philosophy and rationale behind the comprehensive collecting policies of today’s Library of Congress.

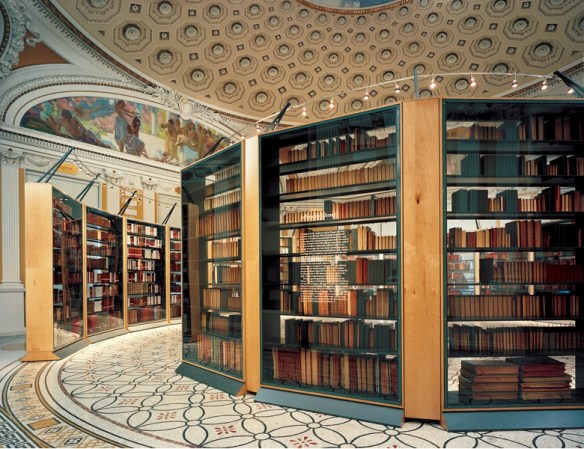

Thomas Jefferson’s Library, permanent exhibit | Library of Congress